-

New York's Highest Court Rules That Auction Sellers May Remain Anonymous

12/20/2013

Earlier this week, the New York Court of Appeals (the state’s highest court) issued a much-anticipated decision upholding the auction industry’s longstanding practice of allowing sellers to remain anonymous. Given the importance of auction houses to the art market, and the importance of consignor anonymity to that market, this decision will likely be greeted with relief by many in the art world.

Earlier this week, the New York Court of Appeals (the state’s highest court) issued a much-anticipated decision upholding the auction industry’s longstanding practice of allowing sellers to remain anonymous. Given the importance of auction houses to the art market, and the importance of consignor anonymity to that market, this decision will likely be greeted with relief by many in the art world.

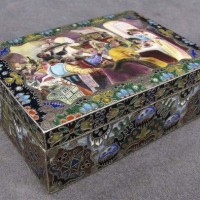

The case arose out of the 2008 auction of a Russian antique silver and enamel box offered for sale by William J. Jenack Estate Appraisers and Auctioneers, Inc. Albert Rabizadeh was the top bidder for the item, but later refused to pay Jenack. Jenack sued for payment and won, but in 2012 a state appellate court reversed, holding that, in order to comply with the state Statute of Frauds—a legal requirement that certain types of documents be memorialized in a signed writing—an auctioneer must disclose the name of the owner who consigned the work. The intermediate court ruled that, because none of Jenack’s documentation identified the seller of the box, Jenack could not enforce the contract and the buyer was not required to complete the sale. The decision caused an uproar in the art world because many sellers at auction prefer to remain anonymous, and most auction houses comply with those wishes (for example, by simply noting that an artwork comes from a “private collection”).

This week, the New York Court of Appeals unanimously reversed the intermediate appellate court. It framed the central issue as “whether the sale of the auction item to Rabizadeh [was] memorialized in a writing that satisfies the Statute of Frauds.” The documentation involved in this particular sale included the following:- An “Absentee Bid Form” that prospective bidders can submit in advance of an auction, to allow them to bid without attending the auction in person. A few days before the auction, Rabizadeh submitted a signed, absentee bidder form wherein he provided all of the information requested by Jenack: his name, contact information, a credit card number, and a list of items—including the box—on which he intended to bid. The absentee bidder form laid out Jenack’s terms for the auction, including the requirement that payment was due within five days of a successful bid. Directly above the signature line, the form included a statement that “Bids will not be executed without signature. Signature denotes that you agree to our terms.”

- Jenack’s “clerking sheet.” This document sets forth a running list of the items presented at the auction (including the item’s lot number, catalogue description, and the number assigned by Jenack to the consignor). At the close of the bidding for each item, the chief clerk records the winning bidder’s assigned bidding number and the amount of the winning bid.

- The invoice sent by Jenack to Rabizadeh after the auction. The invoice reflected the bidding price, the 15% “buyer’s premium” and applicable taxes.

The Court of Appeals concluded that “there exists sufficient documentation of a statutorily adequate writing.” Parsing the statutory language, the Court held that “a bid may satisfy the Statute of Frauds where there exists “a memorandum in satisfaction of GOL § 5-701(a)(6),” which says that, “if the goods be sold at public auction, and the auctioneer at the time of the sale, enters in a sale book, a memorandum specifying the nature and price of the property sold, the terms of the sale, the name of the purchaser, and the name of the person on whose account the sale was made, such memorandum is equivalent in effect to a note of the contract or sale, subscribed by the party to be charged therewith.”

As to the seller, the Court noted that Jenack and various amici curiae had argued that “a requirement that the seller’s identify be divulged would undermine the [entire New York auction] industry.” (According to the Art Newspaper, Sotheby’s was among the amici.) The Court noted, however, that the GOL does not reference the “seller”; therefore, “the seller’s name need not be provided in order to satisfy the requirement of ‘the name of the person on whose account the sale was made.’” The Court further cited longstanding case law that “an auctioneer serves as a consignor’s agent.” It continued, “Here, the clerking sheet lists Jenack as the auctioneer, and as such it served as the agent of the seller. The clerking sheet, therefore, provides ‘the name of the person on whose account the sale was made’” and satisfies the statute, particularly as there was nothing in the record to suggest that Jenack was anything other than the seller’s agent.

As the Art Law Report observed, “The fact remains that no one makes an auction purchase at gunpoint, and if anonymity drives the availability of art, then it is hard to quarrel with.” Furthermore, as the Art Law Report points out, consignor anonymity cuts both ways when it comes to smuggled or looted artworks; anonymous sellers do make it difficult to investigate a work’s provenance, but without anonymity, some objects might never surface on the open market at all. For better or for worse, the Jenack decision allows auctioneers to continue to conceal seller’s identities for the foreseeable future.

Art Law Blog