-

On Appeal, Second Circuit Reverses Fair Use Ruling In Dispute Over Andy Warhol Artwork

03/30/2021

Since 2017, we’ve been following the federal lawsuit between the Andy Warhol Foundation and photographer Lynn Goldsmith; you can read our previous posts about it here and here. In mid-2019, a federal judge in New York dismissed Goldsmith’s copyright infringement claims against the Foundation, ruling that a series of Warhol artworks based on an image taken by the photographer were protected as fair use. But now, the Second Circuit Court of Appeals has reversed that decision, in an opinion that has potentially wide-reaching impacts for the Foundation, for appropriation art generally, and for anyone in the art world who is interested in the ongoing question of how courts handle the difficult concept of fair use.

Since 2017, we’ve been following the federal lawsuit between the Andy Warhol Foundation and photographer Lynn Goldsmith; you can read our previous posts about it here and here. In mid-2019, a federal judge in New York dismissed Goldsmith’s copyright infringement claims against the Foundation, ruling that a series of Warhol artworks based on an image taken by the photographer were protected as fair use. But now, the Second Circuit Court of Appeals has reversed that decision, in an opinion that has potentially wide-reaching impacts for the Foundation, for appropriation art generally, and for anyone in the art world who is interested in the ongoing question of how courts handle the difficult concept of fair use.

Background

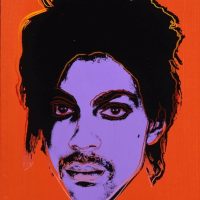

At the center of this suit is a photograph that Goldsmith took during a 1981 photo shoot with musical icon Prince. The photo was never published, but in 1984, Goldsmith’s photo agency licensed the photo “for use as an artist’s reference” in connection with an article to be published in Vanity Fair. The magazine then commissioned Warhol to use the photo to create an illustration of Prince to accompany an article. That Warhol artwork was eventually published in the 1984 issue of Vanity Fair, and Warhol also used Goldsmith’s photo as the basis for several other artworks. Since Warhol’s death in 1987, the Foundation has owned the intellectual property rights to the 16 works that are based on Goldsmith’s photo, although many of the actual works themselves are now owned by third-party collectors.

After Prince died in 2016, Vanity Fair republished online its 1984 article, including Warhol’s illustration, which it licensed from the Foundation. It also published a commemorative magazine focused on Prince, which had a different Warhol Prince work on the cover, also licensed from the Foundation. Shortly thereafter, Goldsmith learned for the first time of the Warhol Prince series and contacted the Foundation. In 2017, after some prelitigation negotiations, the Foundation filed a preemptive lawsuit seeking a declaration that it had not infringed the copyright of Lynn Goldsmith; Goldsmith countered with an affirmative infringement claim.

Following discovery, the parties each sought summary judgment, with the Foundation arguing that the Warhol works were not substantially similar to Goldsmith’s photo and in any case are protected by fair use. In a written decision, U.S. District Judge John G. Koeltl agreed with the Foundation. See Andy Warhol Found. for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith, 382 F. Supp. 3d 312 (S.D.N.Y. 2019). The District Court opted not to rule on the threshold question of whether the works were substantially similar, instead holding that, assuming there was substantial similarity, Warhol’s works nevertheless constitute fair use under the four statutory fair use factors (see here). In doing so, the Court placed emphasis on the concept of “transformativity,” which asks “whether the new work merely supersedes the objects of the original creation or instead adds something new, with a further purpose or different character, altering the first with new expression, meaning, or message.” The District Court concluded that Warhol’s works “may reasonably be perceived to be transformative of the Goldsmith Prince Photograph.” In light of that, the other statutory factors weighed in favor of fair use.

The Second Circuit’s Ruling

Following her summary judgment defeat, Goldsmith appealed to the Second Circuit. And last week, the Second Circuit issued its ruling, which overturns the district court and drastically changes the conversation. See Andy Warhol Found. for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith, No. 19-2420-CV, 2021 WL 1148826 (2d Cir. Mar. 26, 2021). The three judges on the panel each authored an opinion; Judge Gerard Lynch penned a decision for the court, but Judge Richard Sullivan also wrote a concurring opinion (in which Judge Dennis Jacobs joined, meaning a majority of the panel signed onto it), and Judge Jacobs also chimed in with his own concurring opinion.

The court’s primary opinion, in broad strokes, holds that “the district court’s conclusion that the Prince Series works are transformative was grounded in a subjective evaluation of the underlying artistic message of the works rather than an objective assessment of their purpose and character,” and that its error on the first statutory fair use factor was “compounded in its analysis of the remaining three factors.” It concludes that all four factors actually favor Goldsmith; that the Prince Series works are not fair use as a matter of law; and that they are substantially similar to the Goldsmith photo as a matter of law.

Transformativity

In terms of transformativity, the Court emphasized that the key question is how the work may “reasonably be perceived.” The panel noted that the district court relied heavily on the Second Circuit’s 2013 ruling in Cariou v. Prince—and warned that, although the entire circuit “remains bound by Cariou,” the decision has been subject to criticism and is in need of “clarification.” (See here for our original analysis of Cariou.)

First, the Court noted that it is not enough to simply add a new aesthetic or new expression to its source material. Indeed, the Court held that an overly-broad view of transformativity would effectively encroach on statutory copyright protection for derivative works. The Court indicated that in many cases (for example, the Google Books case—see here,here, and here for our posts on that) courts examine whether the secondary work has a plainly different purpose than the primary work, but that that analysis is “less useful” where both works are simply works of visual art. Instead, the Court suggested that, where a secondary work does not obviously comment on the original or use it for a fundamentally different purpose, “the secondary work itself must reasonably be perceived as embodying an entirely distinct artistic purpose, one that conveys a ‘new meaning or message’ entirely separate from its source material.” It also suggested that this standard is more commonly met by works that “draw from numerous sources, rather than works that simply alter or recast a single work with a new aesthetic.”

Applying the above to the Prince photograph, the panel held that the district court’s analysis had placed too much emphasis on the artists’ respective intents, and on the meaning that a critic or judge draws from the work—perceptions that are “inherently subjective.” Rather, the inquiry should have been whether the secondary use of source material is “in service of” a “fundamentally different and new” artistic purposes and character, setting it apart from the raw material from which it draws. It must “comprise something more than the imposition of another artist’s style on the primary work.” Viewed in this light, the Court, held, the Warhol Prince works were not transformative. They may have a “distinct aesthetic sensibility” that many might associate with Warhol, but they have the same overarching purpose and function: a portrait of a particular person. They retain, and do not significantly alter or add to, the “essential elements” of the Goldsmith photo, which “remains the recognizable foundation upon which” they are built.

As a final note on transformativity, the Court emphatically rejected what it called a “celebrity-plagiarist privilege,” declining to find fair use simply because the Warhol works were immediately recognizable as the work of an established artist with a distinctive style. The Court offered the analogy that simply because a film is recognizable as “a Scorsese” does not absolve him of the obligation to license the original book on which the film is based.

The Other Statutory Factors

Moving to the other fair use factors, the Court held that, while the commercial nature of the Warhol works did not factor heavily into its analysis in this case, the Goldsmith photo’s status as both creative and unpublished favored Goldsmith here. As for the amount and substantiality of the use, the Court rejected the district court’s holding that Warhol, through cropping, flattening, and minimizing the use of light, contrast, and shading, had “removed nearly all” the copyrightable elements of the photo. While of course Goldsmith cannot copyright Prince’s facial features, “the law grants her a broad monopoly on its image as it appears in” her photo—and Warhol had not simply used that photo as a reference or memory aid, but had directly copied it to create works that were “readily identifiable as deriving from a specific photograph” of Prince, and indeed in a sense were “depictions of” the photo itself. On this point, the panel distinguished the Seventh Circuit’s ruling on fair use in Kienitz v. Sconnie Nation (see here for our post on that 2014 case), in which a tee shirt design “stripped away nearly every expressive element” from a photograph; here, the panel opined, Warhol left far more of Goldsmith’s detail.

Finally, the Court examined the effect of Warhol’s use on the market for Goldsmith’s original work. Here, the Court recognized that the works occupy different markets, but declined to endorse the idea that the two artists have different markets simply because of Warhol’s fame; to do so would mean that the market harm factor would always “weigh in favor of the alleged infringer as long as he is sufficiently successful to have generated an active market for his own work.” The Court further noted that, as a matter of burden of proof, the artist of the original work may bear “some initial burden of identifying relevant markets,” but fair use is an affirmative defense and the alleged infringer must bear the burden of proving that the secondary use does not compete with the first in a relevant market. And here, there was “no material dispute that both Goldsmith and [the Foundation] have sought to license (and indeed have successfully licensed) their respective depictions of Prince to popular print magazines to accompany articles about him.” In addition, the Court noted that the evidence showed that photographers often grant licenses to create stylized derivative images of their work, and additionally that Goldsmith had in fact licensed this work as an artist reference. In short, the Warhol works “pose cognizable harm to Goldsmith’s market to license [the photo] to publications for editorial purposes and to other artists to create derivative works based on” it. Thus, the fourth factor favored Goldsmith.

Substantial Similarity

Separately, the Foundation had asked the Court to affirm the district court’s ruling on an alternative ground, i.e., that the Warhol works were not “substantially similar” to Goldsmith’s photo. The panel not only rejected this argument, but actually reached the opposite holding. First, although the district court had not made findings on substantial similarity, the panel held that a remand was unnecessary because the question of substantial similarity was “logically antecedent” to the fair use question, and because the panel’s fair use analysis also was highly relevant to the substantial similarity question. Thus, the panel held that the works were substantially similar as a matter of law, reasoning that the “average lay observer would recognize the alleged copy as having been appropriated from the” original work. It was important to the Court’s analysis that Warhol not only concededly had access to the Goldsmith photo, but that he literally copied the photo itself (instead of, for example, attempting to create his own similar image). In the panel’s view, “any reasonable viewer” looking at a variety of photos of Prince would be able to identify Goldsmith’s photo as the source material for Warhol.

Concurrences

Judge Sullivan also filed a concurring opinion in which Judge Jacobs joined. They

highlighted what they believe is “an overreliance” on transformativeness in fair use jurisprudence, and advocated for “renewed focus on the fourth fair use factor,” i.e., “the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.” They cited the risk that the question of transformativity might essentially “collapse the four statutory fair use factors into a single, dispositive factor,” because where district courts find a use transformative, they tend to then discount the other factors. Further, they noted that the Second Circuit, cases like the Google Books case have emphasized that the fourth factor is an important recognition of the fact that copyright is, at its core, “a commercial right.” And the question of transformativity is better viewed as subservient to the fourth factor, in that transformative works are more likely to be fair uses because they are less likely to “act as a substitute” for or damage the market for the original. They cited other recent cases (including TVEyes and Keinitz, as well as the Ninth Circuit’s recent ruling in a dispute over a Dr. Seuss book – see here, here, and here for our thoughts on those, respectively) that, in their view, more properly weight the fourth factor.

Judge Jacobs also wrote separately for the sole purpose of pointing out that the panel’s holding “does not consider, let alone decide, whether the infringement encumbers the [16 original Warhol Prince works] that are in the hands of collectors or museums.” Goldsmith had not sought relief as to any of those third parties, seeking only damages and royalties for licensed reproductions of the works, for example, on magazine covers. He acknowledged that the issue “still looms, and our holding may alarm or alert possessors of other artistic works,” but noted that Warhol’s 16 originals were not “substitutes” for the photograph.

Impact of the Ruling

In broad strokes, this decision represents something of a retreat from Cariou, which the panel characterizes as the Second Circuit’s “high-water mark” when it comes to the importance of transformativity. And it continues the Circuit’s realignment of its fair use jurisprudence to emphasize a more balanced look at all of the fair use factors, especially the fourth.

In many ways, the opinion is a defeat for appropriation artists. The panel’s decision emphasizes that a secondary work must have a wholly new meaning or message—but clearly takes a narrow view of what that means, holding that here, both the photo and the Warhol works were simply portraits of a celebrity. (As one observer notes, this jeopardizes the fair use status of any artwork where the secondary work is “both recognizably deriving from and retaining the essential elements of the copyrighted work,” and where “art theory and art criticism” are needed to explain why the work is transformatively critical of the original.) The panel also suggests a preference for secondary works incorporating many primary works (for example, a collage), noting that, often, secondary works that simply recast a single primary work are more accurately viewed as unauthorized derivative works as opposed to transformative fair uses. And with its rejection of the “celebrity-plagiarist privilege,” the panel squarely attacks the idea that fair use analysis should favor certain artists simply because of their fame and success in the market, instead making it clear that simply recasting a work in an artist’s distinctive and recognizable style is not enough.

In this respect, the decision will also certainly impact the currently-pending fair use litigation involving another mega-star of the appropriation art world, Richard Prince. We have written before (see here, here and here for more) about two lawsuits spawned by Prince’s “New Portraits” project, in which he appropriated Instagram photos posted by other users of the social media platform. Summary judgment motions are pending in those cases, and this Warhol ruling will almost certainly shape the Southern District of New York’s decision on those motions.

Separately, the panel’s ruling contains some helpful language for those invested in the photographic arts. In particular, the Court specifically rejected the idea that photographs have “thinner” copyright protection than other types of expressive works, noting that, while of course a photographer owns no monopoly on a subject, the law does broadly protect the subject’s “image as it appears in” a specific photo, and will not find fair use where a secondary work is essentially simply a “depiction of” the photo. And here, methodology matters; the panel clearly held it against the Foundation that, as a matter of logistics, Warhol had actually copied the photo.

Overall, the decision represents a further layer of complexity—and, some argue, confusion—in the fair use case law of the Second Circuit. The panel stresses the need for objectivity, but an emphasis solely on the formal visual appearance of works potentially means that artworks are stripped of context; and how is a court to evaluate in a purely objective way whether a work has a fundamentally different meaning, given the inherently subjective nature of art? Another scholar recently expressed a hope that perhaps the Second Circuit might consider rehearing this case en banc to lend more clarity. And the Foundation’s legal counsel has already signaled their intent to challenge the decision—perhaps a full Second Circuit or even the Supreme Court will have more to say about this important case, and we’ll continue to follow it.

Art Law Blog