-

Court Rules, Pre-Discovery, That Grinch Parody is Protected Fair Use

10/23/2017

As the holiday season approaches, a federal court in New York has issued an opinion regarding a parody of Dr. Seuss’s classic children’s book, How the Grinch Stole Christmas—and in the process, has reaffirmed how the fair-use doctrine in copyright law relates to parodies of copyrighted works.

As the holiday season approaches, a federal court in New York has issued an opinion regarding a parody of Dr. Seuss’s classic children’s book, How the Grinch Stole Christmas—and in the process, has reaffirmed how the fair-use doctrine in copyright law relates to parodies of copyrighted works.

A Grown-Up Grinch Takes on the Seuss Estate

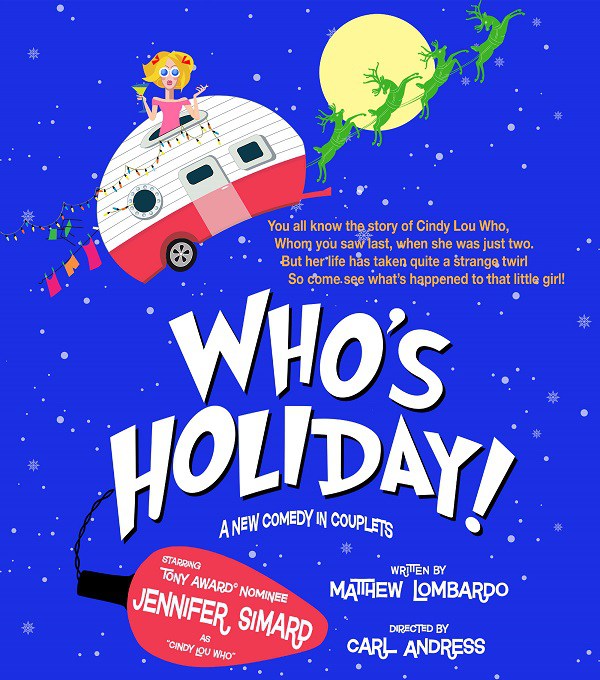

The case involves “Who’s Holiday!,” a one-woman theatrical production whose main character is a grown-up version of Seuss’s beloved character Cindy Lou Who. In Dr. Seuss’s book, little Cindy Lou is the voice of childhood innocence, a foil to the grouchy Grinch and representative of the indomitably joyful spirit of the fictional town of Who-Ville. In the play, Cindy Lou has grown up to become a cynical, ribald, substance-abusing ex-con living a hardscrabble life in an imagined trailer park on the outskirts of Who-Ville.

Last year, a run of the play was canceled after playwright Matthew Lombardo received cease-and-desist letters from the estate of Dr. Seuss asserting that his play violated the estate’s copyright in the original book. Lombardo then sued in federal district court, asking the court to issue a declaration that the play constitutes fair use; the estate filed counterclaims for copyright and trademark infringement. Lombardo then moved for judgment on the pleadings, arguing that the case could be resolved without the need for discovery simply by comparing the works and applying established law regarding the statutory fair use defense to copyright infringement.

Last month, the court sided with Lombardo.

Fair Use Analysis in the Context of Parody

As an initial matter, the court noted that the law does not support a “presumption” that parodies are always fair use; rather, parody, like any other “borrowing” of copyrighted material, is to be analyzed in light of the four fair use factors dictated by the copyright statute. But the court noted that in general, if a work is a parody, the second, third, and fourth factors are likely to lean in favor of fair use.

Next, the court examined the first fair use factor—the purpose and character of the use—and in particular, whether the play really was a parody, i.e., whether its “parodic character” could “reasonably be perceived.” On this point, the court had to determine whether the play commented on the original Seuss work “by imitating and ridiculing its characteristic style for comic effect,” or whether, on the other hand, the play was simply exploiting Seuss’s characters, style, and themes instead of coming up with fresh ideas. The court concluded that the play “subverts the expectations of the Seussian genre, and lampoons the Grinch by making Cindy-Lou's naivete, Who-Ville's endlessly-smiling, problem-free citizens, and Dr. Seuss' rhyming innocence, all appear ridiculous.” The result of the juxtapositions between the Cindy and Who-Ville of the book and their counterparts in the play is to “turn[] these Seussian staples upside down and make[] their saccharin qualities objects of ridicule.” In so ruling, the court reminded readers that whether a parody “is effective, or in good taste, is irrelevant.” It is enough that a work, for example, pokes fun at the original work's hokeyness, blandness or seriousness.

As to whether the play was “transformative” of the original, the court examined whether it

used the original Grinch book “for a purpose, or imbues it with a character, different from that for which it was created." Here, although the play incorporated elements of the book’s characters, setting, and plot, its use (and alteration) of those elements was necessary to the play’s purpose and meaning: “absent that use, much of the Play's comedy and commentary evaporates.”

Having concluded that the play was a transformative parody, the court gave less weight to the fact that the play was a commercial venture, citing case law holding that “Congress could not have intended a rule that commercial uses are presumptively unfair” and that where a work is transformative, its commercial nature is less significant.

As to the second fair-use factor, the nature of the original copyrighted work, the court acknowledged that the original Grinch book’s creative qualities favored the estate, but nevertheless noted that this factor is of limited usefulness in the context of parodies, given that "parodies almost invariably copy publicly known, expressive works.”

As to the third factor, the amount of the original work used by the secondary work, the court began by acknowledging that the greater the taking, the less likely that a secondary use is fair use. It also noted that there is some inconsistency in Second Circuit case law regarding “whether a secondary user may copy more than is necessary to achieve his or her objective.” But, continued the court, in the context of parody, extensive use is often permissible because a parody “must be able to 'conjure up' at least enough of that original to make the object of its critical wit recognizable." Here, the court concluded, the amount the play borrowed from the book was "reasonable in proportion to the needs of the intended transformative use.” The play used elements of Seuss’s original characters, setting, plot, and style, but each had been “distorted” to serve very different functions.

Finally, as to the fourth fair-use factor, the impact of the secondary use on the potential market for the original, the court concluded “there is virtually no possibility that consumers will go see the Play in lieu of reading Grinch” or consuming other Seuss-authorized derivative works such as a film version of the book. “The Play is not an unauthorized sequel of Grinch, and given the clear differences in tone and content, it is unreasonable to assume that audiences might confuse the Play for a theatrical version of Grinch, or that the Play would usurp the market for Grinch.” Similarly, it was unlikely that the estate would ever license such an “un-Seussian" parody of Grinch.

Turning to the estate’s trademark and unfair competition counterclaims, the court noted the importance of balancing trademark rights against the First Amendment, such that federal trademark law "should be construed to apply to artistic works only where the public interest in avoiding consumer confusion outweighs the public interest in free expression." This balancing is particularly important in parody cases (see here for our post about another recent case involving an intersection between trademark and parody), where a parody has to invoke the original, but for expressive purposes and not to commercially exploit the mark. The court concluded that here, the play uses the trademarked Seuss characters, but “the public interest in free expression clearly outweighs any interest in avoiding consumer confusion, the likelihood of which is extremely minimal” given the play’s parodic nature. Likewise, the play’s use of Dr. Seuss-style hand-lettering and images was permissible; the risk of confusion "does not outweigh the well-established public interest in parody."

Parody’s Place in Fair Use Law

This case illustrates that, although fair use can be a complicated and difficult inquiry for courts and litigants alike, the law is somewhat clearer when it comes to parodies of copyrighted works. (Indeed, a parody may be sufficiently original to warrant copyright protection in its own right.) As we noted in our recent post about litigation involving Richard Prince works, courts are sometimes reluctant to resolve fair-use questions without the benefit of discovery, meaning that litigants in fair use cases may be in for a lengthy and costly court battle before the matter is resolved; but here, the court reached its ruling by looking only to the parties' pleadings, the two works themselves, and the relevant case law. While there is no outright “presumption” in favor of fair use when it comes to parodies, defendants in copyright cases may find themselves in safer legal territory if their use of a copyrighted work can be reasonably characterized as a parody.

Art Law Blog