-

Court Rules Against Art Advisor Who Made “Secret Profit” From Sale of Basquiat Work

03/09/2017

Last week, a New York judge granted summary judgment for the estate of an art collector on multiple claims against an art advisor who brokered the sale of the collector’s Basquiat work and, unbeknownst to the seller, pocketed a hefty profit. See Schulhof v. Jacobs, Docket No. 157797/2013 (Sup. Ct. N.Y. Co.).

Last week, a New York judge granted summary judgment for the estate of an art collector on multiple claims against an art advisor who brokered the sale of the collector’s Basquiat work and, unbeknownst to the seller, pocketed a hefty profit. See Schulhof v. Jacobs, Docket No. 157797/2013 (Sup. Ct. N.Y. Co.).

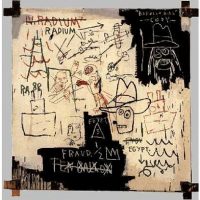

The plaintiff in the case, Michael Schulhof, is the executor for the estate of his mother, Hannelore Schulhof. The defendant is Lisa Jacobs, an art consultant who advises buyers and sellers of modern art. For over a decade prior to Mrs. Schulhof’s death in 2012, Jacobs acted as “a curator and advisor” to Mrs. Schulhof on her significant art collection. According to last week’s court ruling, in October 2011, Michael Schulhof, acting on his mother’s behalf, entered a written contract with Jacobs providing that she would find a buyer for one of Mrs. Schulhof’s works—a Basquiat painting called “Future Sciences Versus the Man.” The contract provided, among other things, that the minimum price for the sale was to be $6 million, and that Jacobs would not accept “any fee from the purchaser, in cash or in kind.” For her services, she would receive from the Schulhofs a $50,000 fee once a sale was consummated. (For her part, Jacobs claims that she also had a separate agreement with Mrs. Schulhof, which entitled her to a “buyers premium,” though no additional evidence was offered that such an agreement existed.)

Jacobs lined up a buyer who agreed to purchase the work for $6.5 million. Jacobs then informed Mr. Schulhof that she had identified a buyer and “was able to get the [buyer] up to 5.5 million” to make the deal. Mr. Schulhof agreed to accept that amount. Jacobs structured the deal as two separate sales, ostensibly to protect the buyer’s anonymity; Mr. Schulhof thus sold the work to Jacobs for $5.45 million, believing that Jacobs would then immediately resell it to the buyer for $5.5 million and keep only her agreed-upon $50,000 fee. In fact, however, Jacobs instead resold the work to the buyer for the price she and the buyer had agreed upon—$6.5 million—and wired to Mr. Schulhof only the amount she and he had agreed upon—$5.45 million—meaning she pocketed the purchase price difference of $1 million, as well as her $50,000 fee.

About a year later, Mr. Schulhof discovered the truth—that the buyer had actually paid $6.5 million (interestingly, he reportedly only learned this information due to a law-enforcement investigation into a totally unrelated theft from the Schulhof collection). He then sued Jacobs, asserting claims for breach of fiduciary duty, fraud, breach of contract, restitution, and unjust enrichment. Following discovery, he moved for summary judgment.

On March 1, the court granted the motion as to all the plaintiff’s claims (except an unjust enrichment claim, which was held to be duplicative of the contract claim). On the fraud claim, the court held there was no real dispute that Jacobs had knowingly misrepresented that the buyer was only willing to pay $5.5 million; that Schulhof had reasonably relied on that misrepresentation in agreeing to the sale; and that he was damaged in the amount of $1 million. Likewise, the court ruled that Jacobs had breached the agreement between her and Mr. Schulhof, under which she was prohibited from receiving any fee from the work’s buyer. Furthermore, on the restitution claim, the court held that, due to her disloyalty, Jacobs had to return not only the $1 million profit, but also her $50,000 fee. The court additionally awarded the plaintiff costs as well as interest on the $1.05 million judgment (which by statute is 9%) running from the time of the sale in November 2011.

Interestingly, the court also held that Jacobs owed a fiduciary duty to the Schulhofs, such that she should have disclosed the buyer’s $6.5 million offer. This stands in contrast to other recent case law in which an art advisor has been held not to be a fiduciary; multiple cases have rejected the existence of a fiduciary duty in art deals based solely on the parties’ longstanding relationship. Here, the court ruled that a fiduciary duty existed due to the longtime relationship between Jacobs and Mrs. Schulhof, in combination with the terms of the October 2011 contract between her and the Schulhofs.

This case is noteworthy because, as another commentator has pointed out, this type of opaque dealing, in which an intermediary advisor or dealer gets paid by both sides of an art transaction, is “more common than one might think.” Indeed, this fact pattern—a collector learning only after the fact that an intermediary, whom the collector thought was working only in the collector’s best interests, pocketed a significant mark-up on a deal—has arisen in more than one case in the last year (see here and here), most notably in the high-profile feud between Russian billionaire Dmitry Rybolovlev and his onetime art dealer, Swiss businessman Yves Bouvier.

Here, the existence of the written contract between Jacobs and the Schulhofs, specifying that Jacobs would not receive payment from the work’s buyer, seems to have been a key component of the Schulhof estate’s victory. But it would have been even better if that contract had included, for example, provisions specifying the nature of the relationship, provisions requiring Jacobs to disclose to the Schulhofs any other documents or agreements related to the transaction (perhaps redacted as needed to protect a buyer’s confidentiality), or other provisions that would have added clarity to the parties’ respective roles and obligations. Proactive contracting prior to a transaction can help avoid disputes, conflicts of interest, and litigation after the fact, especially in art deals involving advisors and other types of intermediaries.

Art Law Blog