-

Thefts Highlight Security Vulnerabilities at Libraries and Archives

07/31/2013

Two recent criminal investigations illustrate the security challenges faced every day by libraries, record depositories, and other collections of books and documents. For reasons discussed below, institutions exploring security options for their archival collections should consult both legal counsel and security experts who can help formulate a strategy that makes sense for an institution’s unique needs.

Two recent criminal investigations illustrate the security challenges faced every day by libraries, record depositories, and other collections of books and documents. For reasons discussed below, institutions exploring security options for their archival collections should consult both legal counsel and security experts who can help formulate a strategy that makes sense for an institution’s unique needs.

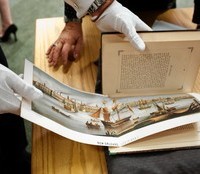

In the summer of 2011, an employee of the Maryland Historical Society called the police after watching a visitor place one of the Society’s documents in his laptop case and then leave the building. The ensuing investigation ultimately uncovered a far larger conspiracy, and two suspects, Barry Landau and Jason Savedoff, eventually pled guilty to charges involving the systematic theft of thousands of historical documents from several different museums, historical societies, and other archival collections across the country. Among the institutions victimized were the William McKinley Presidential Library and Museum in Ohio; the Culinary Arts Museum in Rhode Island; the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum in New York; the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, the Connecticut Historical Society, and the University of Vermont. The stolen items included priceless documents written by major historical figures from Benjamin Franklin to Sir Isaac Newton to Charles Dickens, as well thousands of pieces of presidential memorabilia.

In another recent case, the thefts were, as they say, an “inside job.” Over the course of nearly a decade, a librarian at the Kungliga Biblioteket, the National Library of Sweden, stole dozens of rare books and manuscripts and sold them to a German auction house using an assumed name. The pilfered items went unnoticed until another researcher came to the library seeking a rare volume and the library could not locate it, prompting an inventory procedure that revealed that dozens more “rare or one-of-a-kind books” that were missing. The librarian confessed, and committed suicide a short time later.

In both cases, unlike the stereotypical and oft-fictionalized “museum heist” by armed and masked intruders, these thieves gained access to the collections under the guise of legitimate scholarship. The Swedish librarian was a trained professional tasked with protecting the collection he pillaged. The Americans, Landau and Savedoff, frequently posed as researchers, often going out of their way to ingratiate themselves with the museum staff. In both cases, the perpetrators worked to cover their tracks by stealing not only the items themselves, but documentation that might lead to the items, such as cards from card catalogues, microfilm or other “finding aids” for the document at the museum. They also took pains to erase or destroy any markings or inventory control notations on the documents that might indicate their connection with their rightful home. By making it difficult for a museum to discover that an item is missing, such actions can make recovery more difficult, because by the time the thefts are even discovered, the items may have traveled far and changed hands several times, rendering them very difficult for law enforcement to trace. In the case of the Swedish rare books, only a handful have been recovered; for example, two turned up via a rare book shop in Baltimore, whose owner had no idea they were stolen. Indeed, it’s not a stretch to imagine some of these stolen documents ending up in the collections of other legitimate libraries or universities, donated by well-meaning patrons with no knowledge of their cloudy histories—perhaps creating title disputes and legal headaches down the road.

The cases illustrate the unique security issues faced by institutions in maintaining security for document collections, such as archives, historical societies, universities, and libraries. Institutions are making use of innovative technology, such as cameras, high-tech inventory control systems, catalogue systems that are more difficult to tamper with, or even offering access to digital versions of documents while limiting access to the originals. But the fact remains that archives, libraries, and other document collections have unique vulnerabilities, and their challenges are often compounded by tight budgets, not to mention their mission to make their collections available to researchers and to the public. Moreover, some security measures may raise legal concerns about patrons’ privacy.

Art Law Blog