-

Warhol Foundation Asks Supreme Court To Weigh In On Goldsmith Dispute

After Second Circuit Rejects Its Fair Use Defense01/27/2022

Warhol Foundation Asks Supreme Court To Weigh In On Goldsmith Dispute After Second Circuit Rejects Its Fair Use Defense

Since 2017, we’ve been following the federal lawsuit between the Andy Warhol Foundation and photographer Lynn Goldsmith; you can read our previous posts about it here, here, and here. A few months ago, a revised opinion from the Second Circuit added further complexity to the story. And now, the Warhol Foundation has asked the Supreme Court to give its opinion on whether the fair use defense protects the Foundation from Goldsmith’s copyright infringement claims.

Background

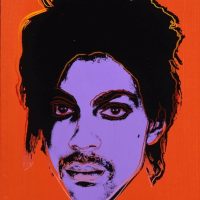

More details are available in our earlier posts, but in brief, this case centers around a photograph Goldsmith took during a 1981 photo shoot with musical icon Prince, which Andy Warhol later used as the basis for several of his iconic pop-art artworks. Since Warhol’s death in 1987, the Foundation has owned the intellectual property rights to the 16 works that are based on Goldsmith’s photo. After Prince died in 2016, the Foundation licensed some of those Warhol works to Vanity Fair, at which point Goldsmith learned of the Warhol Prince series. In 2017, after unsuccessful negotiation, the Foundation sued seeking a declaration that it had not infringed Goldsmith’s copyright in the photo, and Goldsmith counterclaimed for infringement.

On summary judgment, U.S. District Judge John G. Koeltl sided with the Foundation. See Andy Warhol Found. for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith, 382 F. Supp. 3d 312 (S.D.N.Y. 2019). The District Court opted not to rule on the threshold question of whether the works were substantially similar, but held that, assuming there was substantial similarity, Warhol’s works nevertheless constitute fair use under the four statutory fair use factors (see here).

Goldsmith then appealed to the Second Circuit Court of Appeals. And in March 2021, the Second Circuit reversed the district court’s ruling, and instead concluded that the Warhol works were substantially similar to the Goldsmith photo, and that all four fair use factors actually favored Goldsmith; thus, the Second Circuit held, the Warhol Foundation could not invoke the fair use defense as a matter of law. See Andy Warhol Found. for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith, No. 19-2420-CV, 2021 WL 1148826 (2d Cir. Mar. 26, 2021). In its decision, the Second Circuit panel opined that the District Court had placed too much weight on the concept of “transformativity,” which asks “whether the new work merely supersedes the objects of the original creation or instead adds something new, with a further purpose or different character, altering the first with new expression, meaning, or message.” The panel also sought to “clarify” the Second Circuit’s 2013 ruling in Cariou v. Prince, another important fair use decision regarding appropriation art, which also extensively discussed transformativity (see here for our original analysis of Cariou). The Court noted that it is not enough to simply add a new aesthetic or new expression to its source material; rather, where a secondary work does not obviously comment on the original or use it for a fundamentally different purpose, “the secondary work itself must reasonably be perceived as embodying an entirely distinct artistic purpose, one that conveys a ‘new meaning or message’ entirely separate from its source material.” The Court also criticized what it saw as the district court’s overreliance on the artists’ respective intents, as well as subjective perceptions of the work’s meaning. Rather, the panel opined, the inquiry should have been whether the secondary use of source material is “in service of” a “fundamentally different and new” artistic purposes and character, setting it apart from the raw material from which it draw and “compris[ing] something more than the imposition of another artist’s style on the primary work.” Here, in the panel’s view, while the works may have a “distinct aesthetic sensibility” that many associate with Warhol, they have the same overarching purpose and function—a portrait of a particular person—and the Goldsmith photo “remains the recognizable foundation upon which” they are built.

In the Wake Of Google v. Oracle, The Warhol Foundation Urged the Second Circuit to Reconsider

Shortly after the Second Circuit’s Warhol/Goldsmith opinion, the Supreme Court issued a significant fair use decision in a copyright dispute between tech behemoths Google and Oracle. The Supreme Court there held that Google had made fair use of certain software code in which Oracle held a copyright, noting the transformative use of the code at issue and its role in encouraging technological innovation.

In light of Google v. Oracle, the Warhol Foundation asked the Second Circuit for a rehearing (either by the same three-judge panel, or by a larger “en banc” group of judges from the circuit) of the Goldsmith matter, urging that the Second Circuit should reconsider whether its March decision should change in light of the new Supreme Court guidance on fair use.

Second Circuit Panel Issued Revised Decision, Leaving In Place Its Conclusion That The Warhol Works Are Not Protected Fair Use

In late August, the Second Circuit panel issued an amended opinion, which acknowledges Google v. Oracle but concludes that the Supreme Court’s ruling in that case does not alter their overall analysis in the Warhol/Goldsmith dispute.

The panel emphasized that the Google v. Oracle decision comes from a very different context, involving software and computer technology, and that its analysis is of limited usefulness in the context of visual art.

The Second Circuit’s amended decision leaves in place the significant points of its March 2021 ruling. That includes the panel’s admonishment that transformativity must be analyzed with restraint as part of balanced look at all of the fair use factors, especially the fourth factor (“the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work”). That also includes the rejection of what it called a “celebrity-plagiarist privilege,” declining to find fair use simply because the Warhol works were immediately recognizable as the work of an established artist with a distinctive style.

Warhol Foundation Seeks Review By The Supreme Court

At this point, the only option remaining for the Warhol Foundation was to ask the Supreme Court to review the case, by means of a “petition for certiorari.” To do this, the party seeking review must first submit briefing to convince the Supreme Court to take the case; others with an interest in the case may also submit “amicus curiae” (literally, “friend of the court”) briefs to further try to persuade the Court.

It is difficult to make a prediction on whether the Supreme Court will grant certiorari in a given case, because successful petitions are rare; the Supreme Court takes on only a small percentage of the cases for which parties seek certiorari each year. But this case has a few possible reasons why the Court might consider it. First, the Court may be concerned about the Second Circuit's suggestion that the Court's recent Google v. Oracle decision is of limited use in cases outside the software context. If the Court wants to reject that suggestion and make it clear that Google v. Oracle should not be cabined like that, it may be more likely to grant cert here. Second, the Court may appreciate that the uncertainty in the federal courts’ ongoing conversation about transformativity may have the potential to disincentivize certain artistic expression, if artists or galleries may struggle with how to assess the legal risk of a given project; in the interest of ensuring that free speech is not being chilled, the Court may want to try to ameliorate uncertainty about the risk, value, protectability, and economic viability of certain types of art. Finally, the Supreme Court is often interested in resolving so-called “circuit splits,” where different circuit courts are not seeing eye-to-eye on how to approach a particular recurring legal issue; here, the Court may be aware that several federal circuit courts have noted their confusion and disagreement over these concepts for a while now, and the Court may decide that it is time to provide some clarity, to ensure consistency across the circuits’ application of federal copyright law.

What This Ongoing Case Means For The Art World

For the art market, this case represents the courts’ ongoing struggle with the concept of fair use, especially when applied to artworks that incorporate other artworks. Some in the art community have expressed concern that the Second Circuit’s rulings in this case have done little to ameliorate the continuing uncertainty about how fair use applies to visual art that appropriates or borrows significantly from other artists. (Indeed, one commentator notes that the decision focuses on the Foundation’s actions in licensing the Warhol works to be used in a mass-produced commercial magazine; this raises the question of whether Warhol’s original artworks, in the hands of museums and collectors, might involve a very different fair use analysis.)

The “amicus curiae” briefs filed so far reflect the concerns swirling in the art world. The Brooklyn Museum, along with foundations that represent the legacies of artists Roy Lichtenstein and Robert Rauschenberg, have filed an amicus curiae brief in support of the Warhol Foundation. In it, they argue, among other things, that the Supreme Court should clarify the importance of analyzing artworks with reference to their cultural and historical context, and that engaging in a literal side-by-side visual comparison of works “should be where the analysis starts, not where it stops.” They also warn that “the Second Circuit’s reasoning does not just threaten one famous artist’s output with infringement liability—it strikes at the heart of the way artists today have been raised to make and understand art. Whole currents of creative practice would be exposed to litigation and thereby widely discouraged.” Other amici submitting briefs in support of the Foundation include a group of law professors who study art law, copyright, and the First Amendment; their brief criticizes what they see as the Second Circuit’s overemphasis on visual differences at the expense of understanding the meaning of the works, warning that First Amendment case law recognizes that speech can have different meanings to different people. Another law professor’s brief seeks to emphasize the ways in which the Second Circuit’s ruling is inconsistent with other fair use precedent. And a brief submitted on behalf of visual artists and art professors Barbara Kruger and Robert Storr likewise argues that the Second Circuit’s decision will discourage artists from creating new works incorporating existing material, because it threatens the viability of artworks that “recognizably deriv[e] from” or “retain[] the essential elements of” their source material.

What’s Next

Legal counsel for Goldsmith will file a response to the Foundation’s petition on February 11. After that, the Supreme Court will decide to grant or deny the petition. We will continue to closely watch developments in this litigation as well as in the inevitable next dispute over the contours of fair use.

Art Law Blog