-

Family Of Alexander Calder Sues The Family Of His Longtime Dealer

10/31/2013

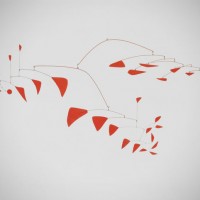

From 1954 until his death in 1976, famed sculptor Alexander Calder was represented by Manhattan dealer Klaus Perls. Over the course of more than two decades, the pair forged a close friendship as well. Their contributions to the art world are formidable; Calder’s groundbreaking mobile works sell for millions of dollars, while Perls was a highly respected dealer and collector who donated more than $60 million worth of masterworks to the Metropolitan Museum of Art prior to his death in 2008. Now, both men are gone, and their families are in court amid allegations that Perls defrauded Calder’s estate and sold dozens of fake Calder works.

From 1954 until his death in 1976, famed sculptor Alexander Calder was represented by Manhattan dealer Klaus Perls. Over the course of more than two decades, the pair forged a close friendship as well. Their contributions to the art world are formidable; Calder’s groundbreaking mobile works sell for millions of dollars, while Perls was a highly respected dealer and collector who donated more than $60 million worth of masterworks to the Metropolitan Museum of Art prior to his death in 2008. Now, both men are gone, and their families are in court amid allegations that Perls defrauded Calder’s estate and sold dozens of fake Calder works.

According to the New York Times, litigation commenced in 2010 after a Canadian gallery contacted the Calder Foundation (which is helmed by Calder’s grandson Alexander Rower) regarding a $1.5 million Calder mobile that had been purchased from the Perls Foundation, a trust formed after the Perls Gallery closed in 1997. Mr. Rower says the work in question had not been listed in the Perls Gallery’s inventory after Calder’s death, and the Calder estate had never received any proceeds from its sale. Further research allegedly revealed several other works in the Perls inventory that were sold without the estate’s knowledge, many consigned by an unknown woman in Switzerland called “Madame Andre.” The Calder estate sued the Perls estate, the dealer’s daughter, and “Madame Andre.”

More recently, the plot has thickened; Calder’s estate is now seeking to amend the complaint to include additional allegations that the Perls family failed to account for literally hundreds of Calder’s works; that Perls sold dozens of fake Calders; and that “Madame Andre” was in fact a nickname for the Perls’ Swiss bank account that was used to avoid tax obligations and to hold some of the ill-gotten sales proceeds. The complaint also asserts that the Perls defendants wrongfully refused to return to the artist’s estate a significant archive of correspondence and records related to Calder’s art. For their part, the Perls defendants have argued, among other things, that the claims in the proposed amended complaint are time-barred; that the mobile that originally sparked this litigation was a gift from the artist to Perls’s wife; that Calder too had a Swiss bank account used to dodge tax obligations; and that Perls would never have knowingly handled a fake Calder work.

This litigation may impact the longstanding legacies of two giants of the twentieth century art world. The case could even spawn future legal actions involving third parties—for example, if there really are fake Calders lurking in collections across the world, concerned owners may begin coming forward with claims. And what if, as the Calder plaintiffs allege, some of Perls’ generous gifts to the Met were purchased with ill-gotten gains? The case will also raise a host of more general questions of interest to the art community, such as who has a rightful claim to an artist’s correspondence and archives. The court is expected to rule soon on whether to allow the plaintiffs’ amended complaint.

Art Law Blog