-

Goldsmith/Warhol Oral Argument At the Supreme Court Underscores the Big Issues—and Weird Wrinkles—Complicating This Case

10/18/2022

Last week, the Supreme Court heard oral argument in the major copyright case of Warhol Foundation v. Goldsmith, which could provide a significant opinion about the “fair use” defense to copyright infringement, with wide-ranging potential implications for the art world—especially appropriation art, photography, and copyright licensing and management. The oral arguments, however, underscore both the magnitude of the questions posed, and the odd aspects of the case’s path to the Supreme Court, which arguably complicate the Court’s ability to grapple with the already-complex issues it presents.

Last week, the Supreme Court heard oral argument in the major copyright case of Warhol Foundation v. Goldsmith, which could provide a significant opinion about the “fair use” defense to copyright infringement, with wide-ranging potential implications for the art world—especially appropriation art, photography, and copyright licensing and management. The oral arguments, however, underscore both the magnitude of the questions posed, and the odd aspects of the case’s path to the Supreme Court, which arguably complicate the Court’s ability to grapple with the already-complex issues it presents.

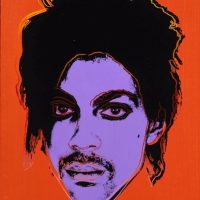

Our previous blog posts contain more detail (see here, here, here, here, and here), but this case centers around a photograph Lynn Goldsmith took during a 1981 photo shoot with musical icon Prince. In 1984, Goldsmith’s photo agency licensed the photo “for use as an artist’s reference” in connection with a planned Vanity Fair article. The magazine in turn commissioned Warhol to use the photo to create an illustration of Prince to accompany a 1984 article about him. Warhol also used Goldsmith’s photo as the basis for additional works, ultimately creating a total of 16 Warhol works depicting Prince. Since Warhol’s death in 1987, the Foundation has owned the intellectual property rights to those 16 works. After Prince died in 2016, the Foundation licensed some of those Warhol works to Vanity Fair, at which point Goldsmith learned for the first time of the Warhol Prince series. In 2017, after unsuccessful negotiations, the Foundation sued, seeking a declaration that it had not infringed Goldsmith’s copyright in the photo; Goldsmith counterclaimed for infringement.

On summary judgment, U.S. District Judge John G. Koeltl sided with the Foundation, holding the works were fair use. See Andy Warhol Found. for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith, 382 F. Supp. 3d 312 (S.D.N.Y. 2019). Goldsmith appealed to the Second Circuit Court of Appeals, which, in March 2021, reversed Judge Koeltl’s ruling and held that all four fair use factors actually favored Goldsmith, so the Foundation had no fair use defense as a matter of law. See No. 19-2420-CV, 2021 WL 1148826 (2d Cir. Mar. 26, 2021). The Foundation then appealed to the Supreme Court. The federal government also participated in the Supreme Court litigation as an amicus curiae (“friend of the court”), largely taking Goldsmith’s side.

What “Use” is At Issue? Just Licensing?

One major wrinkle in this case has to do with exactly what “use” is at issue: the creation of the actual Warhol artworks in 1984 (a claim that is, as Goldsmith concedes, technically barred by the statute of limitations)? Or the Foundation’s licensing of one of those artworks to Vanity Fair in 2016 to accompany an article about Prince’s death? At oral argument, the Court’s questioning was highly focused on the 2016 Vanity Fair article—which is interesting because it is a “use” that necessarily places the works in competition, since Vanity Fair could have chosen to license many images of Prince, including ones from either Goldsmith or Warhol. As Justice Jackson noted, if both Goldsmith’s and Warhol’s works “are going in a magazine for a commercial nature, the purpose, the reason why you've used it, is -- is the same.”

The Warhol Foundation’s attorney (Roman Martinez of Latham & Watkins), however, sought to refocus the discussion on the fact that, “at the moment of creation,” the works had different purposes, and urged that “this case really is not about just the licensing use. This case… is about the creation… this was a dispute over who owns the copyright to these works. [Goldsmith] was asking for an injunction from us that would prevent us not just from licensing the one 2016 work, she wanted an injunction that would prevent us from reproducing, displaying, selling, or licensing [all 16 Warhol Prince] works.” Later, on rebuttal, he reiterated that the case “turns on whether… Warhol acted lawfully or unlawfully at the moment of creation.” He accused Goldsmith’s counsel of “chang[ing] the relief she was seeking,” but clarified that the Foundation had sought (and obtained from the district court) a declaratory judgment as to all 16 [Warhol Prince] works,” so the copyrights in all 16 works are “in play” and “the creation matters.” He also noted that, under 17 U.S.C. § 109(c) (see here), “The reason a museum can display a work… is because it was lawfully made”; if this case holds that the works were not “lawfully made,” that would implicate not just the licensing but what can happen to the actual Warhol artworks themselves.

Conversely, Goldsmith’s lawyer, Lisa Blatt of Williams & Connolly, sought to reassure the Court that the case does not pose a risk to the Warhols hanging in collections and museums: “Goldsmith doesn’t compete in that market… everyone agrees that in museums there’s going to be fair use” because there, Goldsmith “doesn't have market harm” (under the fourth factor of the fair use statute; see here). Moreover, she said that Goldsmith has waived all her remedies “as to museums and to possession and sale” of Warhol’s 16 works themselves, “so all we have here is the commercial licensing.” Pressed by Justice Sotomayor, she clarified this means not just the 2016 commercial licensing of the Orange Prince, but also future “other similar commercial editorial licensing, so in -- for magazine usages.” Arguing on behalf of the government, Yaira Dubin (Assistant to the Solicitor General) also sought to emphasize only the licensing use: “the use at issue here is to depict Prince in an article about Prince.” But Justice Sotomayor again questioned her about other potential commercial licensing applications, such as licensing a reproduction of Warhol’s Orange Prince in an art magazine or a book about Warhol; Dubin indicated that would be subject to a separate analysis of the four fair use factors.

This case thus poses a thorny question about whether the very same artwork can be fair use in some applications but not in others, and if so, how courts should analyze the original “purpose” at the time of creation versus a later “purpose” associated with a particular licensing opportunity. As another scholar recently put it, “as far as I know, no previous court has sliced up something like the creation of a related work into infringing uses and noninfringing uses.”

What About the Other Factors?

The second wrinkle has to do with the limited question that the Supreme Court certified: “Whether a work of art is ‘transformative’ when it conveys a different meaning or message from its source material… or whether a court is forbidden from considering the meaning of the accused work where it ‘recognizably deriv[es] from’ its source material (as the Second Circuit has held).” In other words, the focus of the Supreme Court briefing was on the first factor of the fair use analysis: the “purpose and character” of the use—and in particular, on the idea of “transformativity,” which has been heavily discussed in other copyright cases in recent years (see here and here for examples).

But, as is plain in many fair use cases, the four factors are often closely intertwined, and it is difficult to focus on just one of them to the exclusion of others. The Foundation implored the Court to “make very clear that the Second Circuit’s banishment of meaning or message from the [first factor] inquiry was wrong,” but the oral arguments also frequently veered into discussions of the other three factors, and particularly the fourth factor, which examines whether the follow-on artwork harms the market for the original. As Justice Kavanaugh put it, isn’t the “classic thing [to do] with a photograph [is to hope] that it’ll be used in stories about the subject of the photograph and, therefore, competing in the same market that this adaptation was used in?” And Justice Sotomayor asked Martinez, “why doesn’t the fourth factor just destroy your defense in this case? Meaning you licensed directly to a magazine, which is exactly what the original creator does… So why isn’t that direct competition?” Martinez reiterated that, as noted above, the case is not about just the licensing, but moreover, the parties did not brief the fourth factor before the Supreme Court.

How Should Courts Examine “Purpose” and “Meaning or Message”?

Multiple justices appeared to be open to the idea that the Second Circuit’s ruling was too restrictive in terms of how “meaning and message” should be considered in fair use. But they were still pondering the correct outcome. At times, the Court and parties discussed the possibility that the Court could vacate and remand the case so that a lower court could re-run a full fair use analysis, with appropriate adjustments to the first factor based on the Court’s guidance.

Assuming that meaning or message is supposed to play some role in fair use, the parties and justices also debated how a court should determine art’s meaning or message. Martinez proposed that judges are capable of looking at two works and assessing them in their own judgment, but also that litigants can put forward evidence, including from the original artist, borrowing artist, and experts. Martinez also emphasized that a court need not establish some single true meaning, only “whether a new meaning or message could reasonably be perceived.” The government, however, warned the Court about the perils of a standard of fair use that “requires courts to inquire into the meaning of art,” urging that, “if conveying a different meaning confers license to copy,” then that could render sequels, spinoffs, and adaptations “fair game” as fair use.

Chief Justice Roberts seemed open to the view that the works have very different purposes, musing that, when you look at the two works, “you don’t say, oh, here are two pictures of Prince. You say that’s [Goldsmith’s] a picture of Prince, and this [Warhol’s] is a work of art sending a message about modern society.” Blatt pushed back, urging that in that test “lies madness” because photographs can be so readily altered and edited to make different meanings; she cautioned against putting photography in a particularly vulnerable category where photo copyrights can be infringed “because you can always edit a picture and make these arguments.” She used the example of an airbrushed picture that gives a different message about its subject, but Justice Roberts responded, “I think you would look at both of them, and one would say those are pictures of the same woman. This one may look a little better than that one, but… it’s for the same purpose, it’s to show what she looks like”—unlike the Warhol Prince. The Chief Justice had a similar colloquy with Dubin, suggesting that Warhol’s purpose was “not to show you what Prince looks like”; “if you really wanted to know what Prince looks like, you wouldn’t get that from Warhol’s depiction.” Dubin, however, warned that such a view would eviscerate photographers’ exclusive rights to make derivative works from their creations (see 17 U.S.C. § 106(2)).

Blatt and Dubin asked the Court to focus not on meaning but on justification: “What is the reason or justification to take another’s copyrighted work?” Blatt argued that a “colloquial definition of the word ‘transformative’ is too easy to manipulate.” Both Blatt and the Government did concede that meaning and message can play some role in the analysis, but only to the extent it assists a court in determining purpose and character.

Should Fair Use Analysis Include a “Necessity” Requirement?

The justices pressed Blatt and the government on their suggestion that borrowing artists must show they “needed” to borrow or were “justified” in borrowing another’s work. Justice Kagan expressed skepticism that previous cases contained such a requirement; in her view, earlier precedent “says, well, if you need the original work, that’s the paradigmatic case. But it doesn't say that if you don't need the original work… it can’t be transformative… there’s still the -- the possibility… that, yes, this is fair use because it’s the kind of thing we think of as truly transformative.” Later, she suggested that Warhol arguably fits that bill: “[W]hy do museums show Andy Warhol? They show Andy Warhol because he was a transformative artist because he took a bunch of photographs and he made them mean something completely different… [His work] has an entirely different message from the thing that started it all off.”

In Dubin’s view, “The point is that you have to justify the copying, not just explain why your work is a creative addition to the world of creative additions.” She noted the government’s particular concern about a fair use analysis that eviscerates derivative work rights, “because so many derivative works can be described as conveying new meanings or messages.” After all, she pointed out, many creative people produce highly creative derivative works (citing film directors like Spielberg and Scorsese), but without a “justification for copying, they need to get a license.”

At one point, the justices sought to pin down the government’s proposed formulation of this “necessity” requirement,” ultimately settling on the phrase, “necessary or at least useful in order to achieve a distinct purpose.” And Blatt indicated that she was “okay with” such a rule. On rebuttal, Martinez noted that this idea of “usefulness” had not been briefed before the Court, and argued: “If you thought that that was some sort of requirement, at a minimum we would need to have a fair opportunity to satisfy that requirement, once you tell us what the law is.” He also argued it should not be enough for the original artist to show that the follow-on artist could have borrowed someone else’s work instead; “it can’t be the case that [Goldsmith’s] answer is that [Warhol] should have borrowed from someone else and then we’d be having the same case with a different photographer.”

Looking Ahead

From the perspective of the photography world, it would be problematic if the Court issues a decision suggesting that any artistic rendering, editing, or modification, of a photograph could bring it within fair use; that would threaten erosion of a photographer’s exclusive right to control the making of derivative works based on their photos. From the perspective of appropriation artists and other who incorporate others’ creations as part of their own art, it would be problematic if the Court essentially requires such artists to obtain a license from any earlier creator in order to use preexisting works. And from the perspective of anyone managing intellectual property rights, the case poses the potential for difficult questions about whether there might be some licensing opportunities that are not fair use, while others (for the very same work!) are. The Court is faced with complex questions against a unique backdrop that arguably further complicates the issues. We will await the decision, which will likely come sometime in the first half of 2023.

Art Law Blog