-

NFTs In the Courtroom: A Look At Some Recent NFT-Related Litigation

02/06/2023

Almost two years ago, we shared some thoughts about the NFT market, how it might interact with the traditional art market, and what questions and issues it might raise as it develops. Now, we are watching with interest as an early wave of NFT-related litigation begins to make its way through the courts. In this update, we explore some of the legal disputes that are applying established law to this new context, and raising novel questions for courts to decide.

Almost two years ago, we shared some thoughts about the NFT market, how it might interact with the traditional art market, and what questions and issues it might raise as it develops. Now, we are watching with interest as an early wave of NFT-related litigation begins to make its way through the courts. In this update, we explore some of the legal disputes that are applying established law to this new context, and raising novel questions for courts to decide.

Challenges of Anonymity in the NFT Market

One major challenge that potential litigants in NFT-related disputes face is that they may not even know the identity of other potential parties. As we explained in our previous post, blockchain transactions are transparent in that they are publicly viewable, but they are usually tied only to a “wallet” account used for holding cryptocurrency and assets; it is often difficult to tie that wallet to a real-world identity. This means that a would-be plaintiff may not be able to determine whom to sue, or how to serve them (a necessary step to initiate a legal action in the first place).

In one recent New York case, a plaintiff, sued several “John Doe” defendants over the hacking of a wallet resulting in the theft of virtual assets worth about $8 million. The plaintiff sought a temporary restraining order and a preliminary injunction to, among other things, prevent the defendants from disposing of the assets while the case was pending—but who could the plaintiff serve? A state court created a work-around by authorizing a plaintiff to serve court papers via an “air drop” (a form of automatic transfer) of a “service token” to the anonymous defendant’s crypto wallet. Subsequent court filings indicate that the notice was received, and indeed, a law firm filed a notice of appearance on behalf of the Doe defendants. The case has since settled. While courts around the country may not all agree about whether this method of service is sufficient, the case represents one court’s approach to what is likely to be a frequent problem in crypto-related lawsuits. (See also here and here for information about another case brought in Singapore, in which the court issued a freezing injunction to prevent the sale of a purportedly stolen NFT.)

Claims Against Parties Other Than the Scammers

Other litigants who have lost valuable NFTs due to scams, hacks, or phishing have taken another approach: rather than go after the perpetrators of a scam directly, they are pursuing other companies in the NFT ecosystem who, they claim, should have prevented the theft of the victim’s property.

For example, in one case, filed last year in a Texas federal court, the plaintiff sued OpenSea, a major NFT marketplace, claiming that he lost his NFT property due to a phishing scam that was exploiting a known bug or loophole in the OpenSea interface; he brought causes of action including contract claims, negligence, and breach of fiduciary duty, arguing that OpenSea breached its duty of reasonable care to him as a user and failed to take proper measures to protect users from security threats. However, there is an arbitration clause in the OpenSea terms of service, so OpenSea has asked the court to send the case to arbitration instead; that motion is still pending.

In another case, filed in federal court in Nevada, a plaintiff sued Yuga Labs (the creators of the famed “Bored Ape Yacht Club” collection of NFTs), OpenSea, and another NFT marketplace called LooksRare. Armijo, the plaintiff, alleges that, when scammers stole his Bored Ape NFT, the marketplaces failed to do enough to stop the scammers from reselling the stolen goods. He also points out that holders of BAYC NFTs can access a number of “perks” associated with Ape ownership, and urges that Yuga Labs has failed to implement security measures to prevent holders of a stolen ape from accessing and exercising those perks. Last week, however, the court dismissed the claims against Yuga Labs on jurisdictional grounds. The court also rejected the claims against OpenSea, which were all negligence-based, citing the “economic loss doctrine,” which is followed by many states and provides that there is generally no negligence liability when a plaintiff seeks to recover “purely economic losses,” as opposed to damages involving physical harm to a person or property. Armijo had urged that the benefits of owning an Ape are not solely economic, citing “social and experiential” benefits, but the court was not persuaded, noting that most of the “perks” are economic in nature (such as exclusive merchandise, event tickets, and free cryptocurrency and NFTs), and further, that because membership in the BAYC Club is directly tied to owning an Ape, it is more appropriately characterized as a “benefit of the bargain” loss. The remaining defendant, LooksRare, was served by mail but has not responded to or participated in the litigation, and Armijo has indicated it may seek permission to use an alternative means of service to try to reach the company, whose founders, directors, and officers are anonymous.

Stepping back, these cases represent an attempt to establish what NFT marketplaces and creators owe to their consumers in terms of measures that can prevent or rectify fraudulent activity by wrongdoers. Plaintiffs so far have encountered significant challenges, but the fact of these lawsuits may well put pressure on market actors to consider ways to protect their users.

Intellectual Property Disputes Abound

Another major category of NFT-related litigation involves NFTs that allegedly infringe on someone else’s intellectual property, such as a copyright or trademark. In one example, Yuga Labs, creator of the Bored Apes, has sued a conceptual artist who created his own line of ape NFTs; he claims they are satire and a form of appropriation art, while Yuga claims they are trademark infringement. That case is currently in discovery.

In another example, in late 2021, movie studio Miramax sued Hollywood writer and director Quentin Tarantino over his plan to sell NFTs associated with “high-resolution scans from his original handwritten screenplay of Pulp Fiction, plus a drawing inspired by some element of the scene.” Tarantino argued that in his contract with Miramax, he had retained screenplay publication rights, and that the NFTs were simply a way to republish his script in a new format. Miramax, for its part, asserted that the contract gave it rights to media that had not yet been developed in 1996, and that that should include the NFTs. The case has since settled.

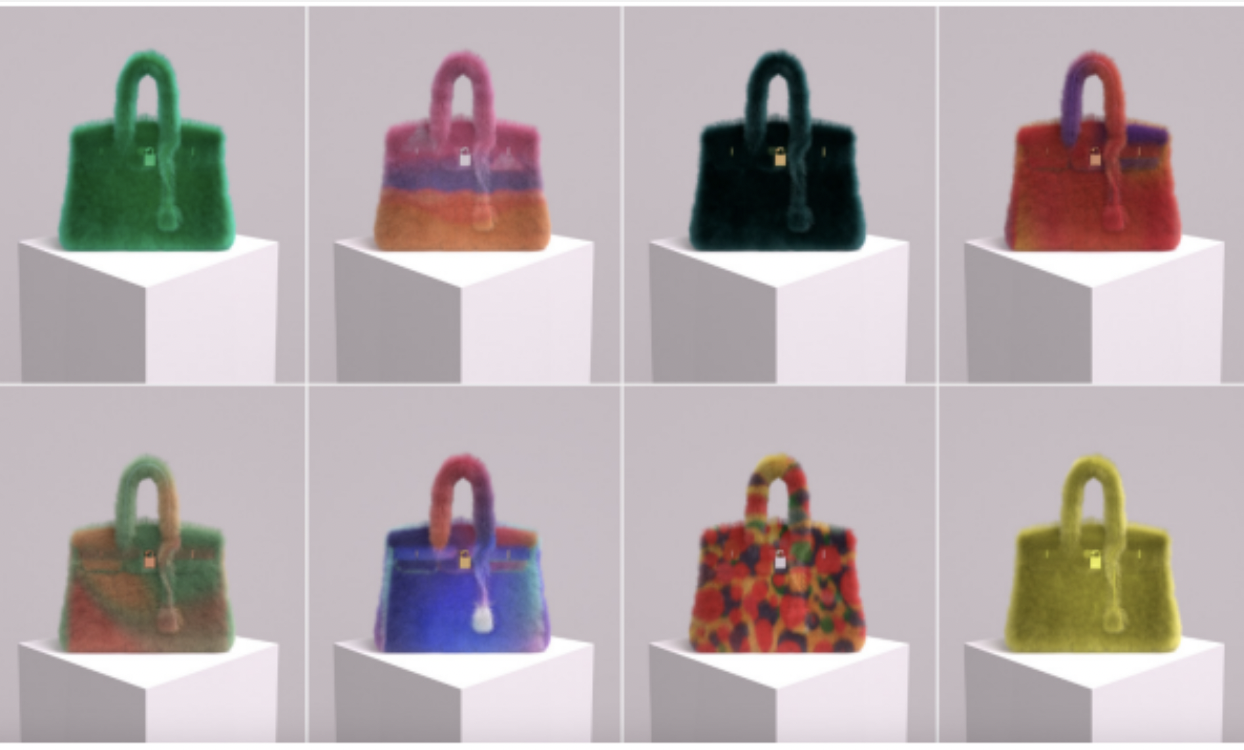

And in late January, a high-profile NFT lawsuit actually went to trial before a jury in New York. In that case, fashion house Hermès has sued digital artist Mason Rothschild over his creation of “MetaBirkins,” NFTs depicting digital images of the iconic Birkin bag that has long been a fashion status symbol and a mainstay of the Hermès brand. Hermès has alleged trademark infringement, urging that consumers were misled into believing that Hermès had created or at least endorsed the MetaBirkins, and further, that it has damaged the fashion house’s ability to enter the NFT space itself. Rothschild has argued that his NFTs are artistic expression and cannot be the basis of trademark liability. The docket indicates that the trial is now complete but the parties and the court are still hashing out jury instructions.

These cases raise significant questions about how metaverse assets like NFTs interact with trademark and copyright law that has largely developed around physical goods and traditional intellectual property. They also implicate larger ideas about free expression and how to decide whether an artist is commenting on a preexisting brand or artwork versus simply infringing upon it—topics that also have resonance in the extensive conversations happening around fair use in the art world today.

This is by no means a comprehensive list of all the current NFT litigation happening right now. (For example, see here for a discussion of some currently-pending litigation in which courts may need to examine whether and to what extent NFTs should be treated as securities under the law.) Rather, we have simply highlighted some cases that raise interesting questions for those involved in the art market. We will continue to monitor litigation in the NFT space as it evolves.

Art Law Blog