-

Jeff Koons Sued For Copyright Infringement, Again

01/10/2016

Famed “appropriation artist” Jeff Koons was sued in federal court last month over his alleged copyright infringement of a photograph used in a 1986 liquor advertisement.

Famed “appropriation artist” Jeff Koons was sued in federal court last month over his alleged copyright infringement of a photograph used in a 1986 liquor advertisement.

Koons is no stranger to litigation, having been sued on several different occasions for his appropriation art. The results of those suits have been mixed. For example, one of his works, “String of Puppies,” in which he created a sculpture based on a photograph without permission from the photographer, became the subject of an important court decision when the Second Circuit rejected Koons’s argument that his copying of the photograph was protected by the fair-use doctrine. See Rogers v. Koons, 751 F. Supp. 474 (S.D.N.Y. 1990), aff’d, 960 F.2d 301 (2d Cir. 1992). Conversely, he prevailed in a different case where his use of a fashion photographer’s image of a set of legs as part of a collage was held to constitute fair use. See Blanch v. Koons, 467 F.3d 244 (2d Cir. 2006).

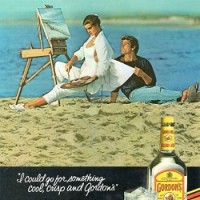

The new case, Gray v. Koons (S.D.N.Y. Docket No. 15-cv-9727), was initiated by commercial photographer Mitchel Gray, who in the mid-1980s created a photograph of a couple on the beach, where the woman was painting at an easel while the man watches. Gray’s complaint alleges that he granted Gordon’s Dry Gin a limited-use, limited-duration license to the photograph, and the company then used it in a 1986 print advertising campaign. According to the complaint, in 1986, Koons (without consulting, crediting, or compensating Gray) reproduced the photograph in its entirety in a painting, along with other elements of the Gordon’s advertisement (a gin bottle, a glass, and a slogan) that were slightly modified (for example, Koons used a different font and placement for the ad components and slightly changed the wording of the slogan). The Koons work, “I Could Go For Something Gordon’s,” became part of a Koons series, “Luxury and Degradation,” that also included reproductions of a number of other liquor advertisements. Koons produced two editions and one artist’s proof of the work. In 2008, the artist’s proof was sold through auction house Phillips, for more than $2 million; Phillips has also allegedly displayed the image on its website since the auction.

Gray’s primary claim is against Koons for copyright infringement. There is also a claim against an unnamed collector who owned the artist’s proof of the Koons work prior to the 2008 Phillips auction, on the grounds that the collector “publicly displayed, distributed, and sold a work derived from and containing a near-identical reproduction of” Gray’s work without his permission, and participated in the auction. Gray names Phillips as a defendant, both for displaying the work on its website and for its role in the auction. Gray seeks damages and disgorgement of the defendants’ profits from the sales of the work. He additionally seeks injunctive relief, among other things, preventing the defendants from displaying the allegedly infringing work, and asks the court to direct Koons to hand over any infringing materials, recall any infringing works currently on the market, and contact all current owners of the infringing works to inform them that such works “may not be lawfully sold, distributed, or publicly displayed.”

The defendants have not yet responded to Gray’s complaint. But one issue likely to be raised in early stages of the litigation is the timeliness of Gray’s claims, including for purposes of the three-year statute of limitations for copyright infringement claims. Gray says he only learned about Koons’s copying in July 2015. But, as one commentator has already pointed out, the plaintiff is walking a fine line in terms of his timing; he alleges that the Koons image was “only occasionally displayed publicly,” which is why he didn’t learn of the infringement for nearly three decades. On the other hand, his claim against Phillips is founded in part on allegations that Phillips has displayed the Koons image on its website since the 2008 auction.

A central issue, though, will likely be whether this particular appropriation is protected by the fair-use defense to copyright infringement (see 17 U.S.C. § 107). The landmark Second Circuit decision in 2013’s Cariou v. Prince case, which held in favor of fair use for famed appropriation artist Richard Prince, placed significant emphasis on whether the artist’s use of the photographs he copied was sufficiently “transformative” to qualify as fair use. Since the Cariou decision, at least one other appellate court has warned against putting too much emphasis on transformativeness when that concept appears nowhere in the copyright statute. Another recent Second Circuit case also examined the concept of “transformativeness” (although not in the context of visual art specifically), and cautioned against “oversimplified reliance” on the term, noting that transformativeness “does not mean that any and all changes made to an author’s original [work] will necessarily support a finding of fair use.” Rather, a “would-be fair user of another’s work must have justification for the taking.”

Gray may seek to argue that Koons had no justification for taking Gray’s work without permission; for example, Gray’s complaint takes care to emphasize that Prince himself has said that his works are not “making a critique” of the works he appropriates. The plaintiff will also likely emphasize the Cariou court’s examination of the way in which Prince’s works “manifest[ed] an entirely different aesthetic from” the photographs Prince copied, including differences in mood, “composition, presentation, scale, color palette, and media.” In contrast, the plaintiff here will likely argue that Koons’s changes to Gray’s work are minimal.

The presence of additional defendants—Phillips auction house and a previous owner of the Koons work—may also raise important questions about whether and how parties other than the appropriation artist might be held liable in connection with the artist’s alleged infringement. As another art-law expert points out, the Cariou v. Prince case also named as a defendant the Gagosian Gallery, which displayed Prince’s allegedly infringing works; however, the case did not end up exploring Gagosian’s potential liability since the case settled after the court ultimately held that most of the works were protected by fair use.

We will continue to follow this case as it unfolds, as it has the potential to add to the complex ongoing conversation about fair use of appropriated works in visual art.

Art Law Blog