-

Two New Lawsuits Filed Against Major Museums

Over Works Lost During Nazi-Era Persecution01/30/2023 In recent weeks, the families of two different victims of Nazi persecution have filed suit in federal court, each suing a major museum over artwork taken from their ancestors during the Nazi era. These cases continue to raise complex legal questions about the painful legacy of a brutal regime and its massive displacement of art throughout Europe during the years before, during, and after World War II.

In recent weeks, the families of two different victims of Nazi persecution have filed suit in federal court, each suing a major museum over artwork taken from their ancestors during the Nazi era. These cases continue to raise complex legal questions about the painful legacy of a brutal regime and its massive displacement of art throughout Europe during the years before, during, and after World War II.

The Stern Family’s Lawsuit Against the Met Over Nazi-Looted Van Gogh

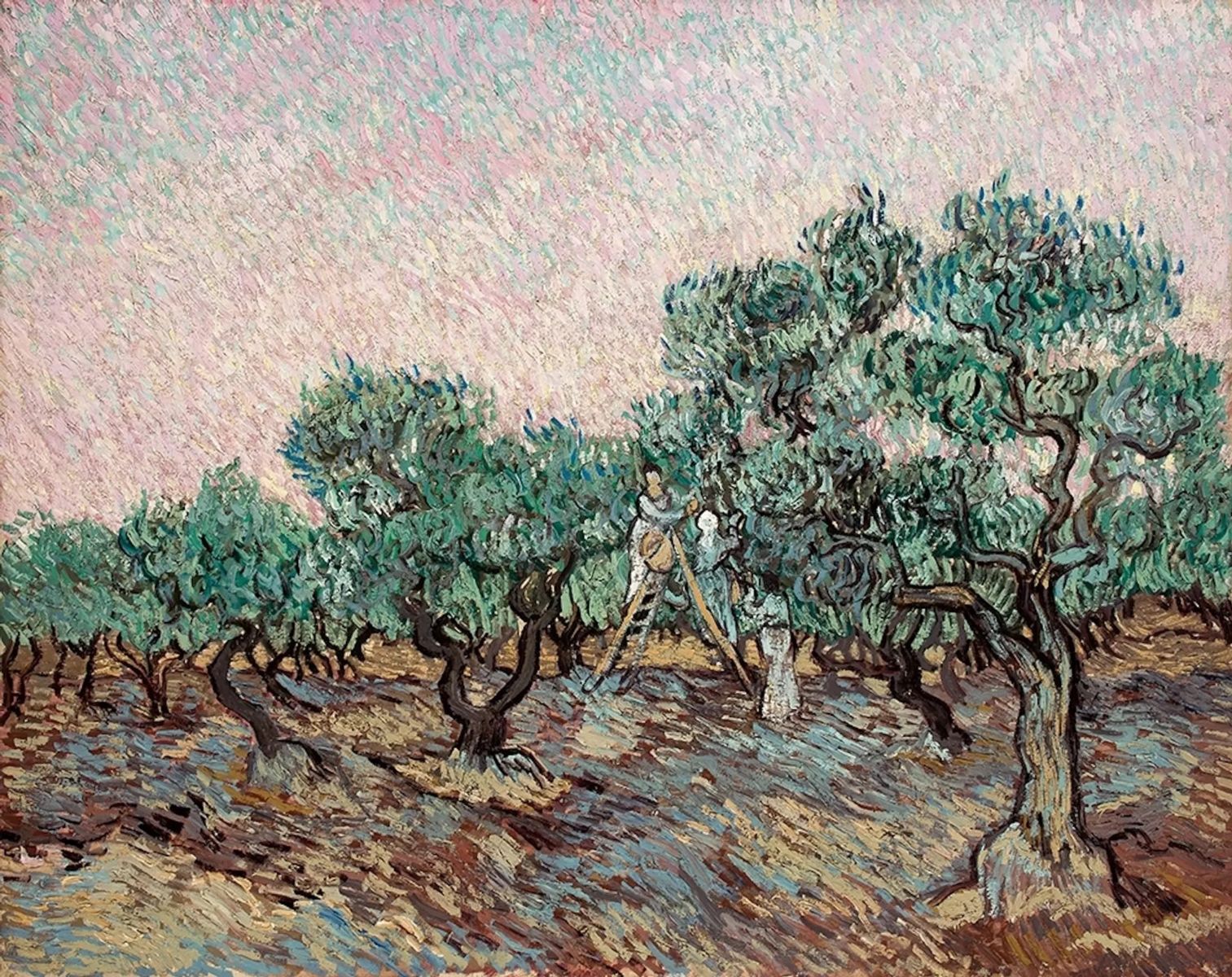

In a complaint filed in mid-December in a federal court in California, the descendants and heirs of Hedwig Stern asserted claims against New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art related to their family’s loss of a Van Gogh artwork during the years before World War II.

According to the complaint, Stern was a German Jewish woman who was forced to flee Germany in 1936 as persecution of Jewish families by the Nazi regime ramped up. (While World War II did not begin in earnest until 1939, the Nazi regime took power in Germany in 1933, rapidly turning it into a one-party totalitarian dictatorship, and almost immediately began stripping Jews of basic rights and property.) The family alleges that when Stern left Germany, the Gestapo stopped her from taking the Van Gogh and other artworks with her. The Nazis then handed her art and other property over to a “trustee” to be liquidated. In 1938, the Painting was sold through an “Aryanized” gallery to a German collector named Theodor Werner. (Aryanization was a process used by the Nazi regime in which control of Jewish-owned businesses was involuntarily turned over to non-Jews; in this case, the Thannhauser Gallery, owned by Jewish dealer Justin Thannhauser, had been Aryanized.) Werner also acquired some of Stern’s other art as well. The proceeds of the sale were put into a blocked account which the Sterns could not access, and by 1939, the Gestapo had confiscated the account.

After World War II ended, the Sterns (who had relocated to Berkeley, California) sought the return of their art, including by meeting with the U.S. Army’s Monuments, Fine Arts and Archives Division (sometimes called the “Monuments Men”). They eventually got one artwork back from Werner, but not the Van Gogh. Instead, by 1948, the Van Gogh was moved to Paris and then to New York, where Justin Thannhauser, who was by then dealing art in New York, purported to sell it to Vincent Astor, son of an American business magnate. In 1956, Astor sold it to the Met. Finally, in 1972, the Met apparently sold it to Greek shipping tycoon Basil Goulandris and his wife; they later transferred it to their eponymous non-profit foundation, which now operates at least two Greek museums and which has displayed and loaned the painting.

The Stern family alleges that, at the time of the 1948 sale to Astor, Thannhauser knew the work had been looted, because he had personally known Werner and Stern and was aware of her flight from Germany. They further assert that, when the Met bought it in 1956, the Met knew there was a cloud on the work, because its then-curator, Theodore Rousseau was at the time already an expert on Nazi looting; he had longtime ties to the “Monuments Men” and had specifically studied the problem during his World War II work with the OSS (the American “Office of Strategic Services,” a precursor to the CIA). Rousseau, the Sterns claim, “knew or consciously disregarded” that the Van Gogh (a work that had been prominently declared “degenerate” by the Nazis) had been taken from the Sterns by the Nazi regime. Indeed, they note that the Met itself had published a new Van Gogh catalogue raisonné in 1967, which omitted the Sterns’ claims from the work’s provenance, while acknowledging that the work had been in Germany from 1912 to 1948. Against this backdrop, they allege that, when Rousseau approved the Met’s 1972 sale of the Painting to the Goulandrises, he did so in order to avoid giving it back to Stern and to conceal that the Met had known throughout its ownership that the work was looted. The complaint further notes that the Met has restricted public access to some of Rousseau’s archives, stating they will not be available until 2073 (100 years after Rousseau’s death).

The Stern Heirs (who now live in California, Washington, and Israel) are seeking the return of the Painting itself from the Goulandris Foundation. They are also asserting an “unjust enrichment” claim against the Met, seeking restitution of the money that the Met received when the Met sold the Painting in 1972 to the Goulandrises. The Stern Heirs allege that, because the Met knew the Painting had likely been looted by the Nazis, and sold it in order to avoid being forced to return the work to the Stern family and to conceal the Met’s knowledge of the painting’s tragic history, the Met should not be permitted to keep the proceeds of that sale. They also assert a conversion claim against both defendants, seeking damages equal to the value of the painting as well as punitive damages.

The Adler Heirs’ Lawsuit Against the Met Alleges Duress Sale of Picasso

In mid-January, the heirs of another German Jewish art collector, Karl Adler, filed a similar suit in a Manhattan state court, this time against New York’s Guggenheim. They allege that Karl and his wife Rosi bought a Picasso oil painting in 1916, when Karl was an affluent manufacturing executive. But by 1938, persecuted by the Nazi regime, Adler had been forced to give up control of his company (which was then Aryanized), and he fled with Rosi and their son. The complaint explains that the Adlers were desperate to liquidate valuable assets for cash, which they needed in order to pay an onerous “flight tax” imposed on Jews leaving Germany, and to obtain short-term visas to leave the country. As part of this effort, he sold the Picasso for well below its value. The Adlers traveled to several European countries, before finally obtaining a permanent visa for Argentina. Their bank accounts remaining in Germany were frozen, diminished by the forced payment of “atonement taxes” levied on Jews, and eventually the remainder was seized.

Interestingly, the Adler heirs’ story and that of the Stern family have a common character: Justin Thannhauser. The Adlers apparently originally acquired the work from the Thannhauser Galerie in Munich, which at the time was run by Justin’s father. And in 1938, when the Adlers were fleeing Germany, Adler sold the painting to Justin Thannhauser, who by then was living in France. The complaint urges that Thannhauser knew he was getting the Picasso for a “fire sale” price due to the Adler family’s desperation; indeed, they note, Thannhauser seems to have done the same thing with other German Jews who needed to sell art to flee Germany. He bought this work from the Adlers for about $1550 in October 1938, but within the next year loaned it to two museums with insurance valuations of $20,000 and $25,000. Thannhauser brought the work with him to New York when he emigrated there in 1939, and in 1963, he informed the Guggenheim that he would bequeath the painting to the museums upon his death; after he died in 1967, his significant art collection indeed landed at the Guggenheim. The Adler heirs began researching their ancestors’ art in 2014 and demanded the work back in 2021. They assert claims for replevin (i.e., the return of the work), conversion, and unjust enrichment, and they seek a declaration that they have good title to the painting. For its part, the Guggenheim has asserted that it spoke to at least one Adler heir about the work in the 1970s, and he raised no issue at that time.

Key Legal Issue: Thannhauser

Justin Thannhauser is a key figure in the stories of both of these artworks. Thannhauser was undoubtedly an important art dealer and collector, and faced Nazi persecution himself, but he has now been linked to multiple sales of artwork by fleeing Jewish families who have later claimed they sold their art under duress. Indeed, these are not the first lawsuits involving artwork that passed through his hands; for example, in 2009, the Guggenheim settled claims by another family who claimed their art was sold to Thannhauser under duress. Given Thannhauser’s long career on both sides of the Atlantic before, during, and after the war, it is possible that the outcome of these lawsuits could have implications for other works he handled as well. Speaking more broadly, these cases highlight why provenance research is crucial for art buyers; in some situations, the mere presence of a problematic name (for example, a particular dealer or gallery) in a work’s provenance may signal a need for further research.

Key Legal Issue: The HEAR Act

Both cases potentially implicate the Holocaust Expropriated Art Recovery Act of 2016 (the “HEAR Act”), which sought to ensure that claimants to Nazi-looted art are not unfairly barred from pursuing artworks by state statutes of limitations. To do this, the law created a uniform nationwide statute of limitations, providing that “a civil claim or cause of action against a defendant to recover any artwork or other property that was lost during the covered period because of Nazi persecution may be commenced not later than 6 years after the actual

discovery by the claimant or the agent of the claimant of— (1) the identity and location of the artwork or other property; and (2) a possessory interest of the claimant in the artwork or other

property.”

The Adler heirs allege that they did not know about their interest in the painting until at least June 2014; they argue that that fact, combined with a tolling arrangement with the museum, means their suit is timely under the HEAR Act’s provision that a suit must be brought within six years of the “actual discovery” by the claimant of “the identity and location of the artwork” and their “possessory interest” in it. Alternatively, they argue that their claim is timely under New York’s statute of limitations for replevin, which runs for three years from when a claimant makes a demand for the work’s return and is refused.

The HEAR Act’s statute of limitations provisions sunset in 2026, but these cases illustrate that claimants are still coming forward with claims that might at least arguably have been barred under some states’ statutes of limitations.

Key Legal Issue: Laches

While these cases are both in their earliest stages of litigation, it seems likely that the defendants will raise the defense of “laches.” Laches is an equitable defense to some title claims, which a court may apply if it concludes that (1) the claimants were aware of their claim to the property, (2) they inexcusably delayed in taking action, and (3) the possessor was prejudiced as a result. This defense is frequently an issue in Nazi-era art disputes, but it is also frequently raised in other art cases as well (see here for one recent example of a case handled by the Grossman team in which laches was an issue). It is distinct from the question of whether a claim was timely under a statute of limitations, and courts can take into account a wide range of “equitable” considerations unique to each case in applying laches.

As we have discussed before (see here) at least one federal court has ruled that, while the HEAR Act preempts any state statute of limitations that would provide a claimant with less time to bring their claim than they would have under HEAR, federal law does not eliminate a defendant’s ability to raise a laches defense. At least one New York state court, however, has reached the opposite result, concluding that a defendant in a Nazi-looted art case could not even put forward a laches defense, citing the HEAR Act’s directive that actions brought within six years are timely “[n]otwithstanding any defense at law relating to the passage of time.”

In these new cases against the Met and Guggenheim, we once again have a state court and a federal court that will need to consider whether and how the HEAR Act impacts any potential laches defense. Additionally, because laches is a key issue in many art title disputes that have nothing to do with World War II-era provenance, the art law community generally will watch with interest to see how these cases discuss and apply laches case law.

Art Law Blog